The Christiaan Brunings is a sailing monument waiting for you to experience it at the jetty alongside The National Maritime Museum. The ship was built in 1900 for the national Department of Waterways and Public Works (Rijkswaterstaat) as an icebreaker, but, rather uniquely for the time, was built with a very luxurious interior to allow her to serve as an executive vessel as well. She was named after Christiaan Brunings, the Dutch marine engineer recognized as the founding father of the department.

the story of the S.S. Christiaan Brunings

In 1900, when the last nuts and bolts had been tightened on the icebreaker Christiaan Brunings, she didn't bear the name that we know her by today. Then-Minister of Public Works, Trade and Industry Cornelis Lely had approved naming the ship after the famous marine engineer (1736-1805), but the decision became mired in red tape. As a result, the ship was launched in 1900 with a different and much more utilitarian name: De IJsbreker (the Icebreaker).

The Department of Waterways and Public Works originally had the ship built as an icebreaker that could also serve as an executive vessel, which explains the ship's luxurious interior. This dual function was dictated by purely practical considerations: after all, why would you let such a significant investment lie idle for most of the year? The government had had good experiences with a ship previously built for the same dual purpose, the Achilles (launched in 1894).

Icebreakers like the Christiaan Brunings have been used as far back as the 17th century. Drawings from that time show ships like these, made of wood. Their upward-curving bows and flat forestays with iron plating were drawn by horses (sometimes up to twenty!) through ice-covered canals. With each pull, the bow would be drawn up from the water to fall back onto the layer of ice, cracking the ice under its weight. This principle changed little through the centuries, although more and more powerful ships were sought to do it.

Up until the time of the Achilles and the Christian Brunings, the Department hired icebreakers from private parties. The decision to build their own ships was primarily dictated by cost considerations. By this time, fighting ice had become one of the government's standing tasks, one that in the second half of the 19th century had become a crucial part of preventing dike breaks and floods.

lowest bidder

For the construction of the Christiaan Brunings, the Department put out a call for tenders, as was only proper for a government project. Chief engineer N.A.M. van der Thoorn of the 4th River District in Dordrecht asked no fewer than fifteen shipyards to submit bids for 'a propeller-driven steamship for breaking river ice.' The lowest bidder, at 49,400 guilders, was Jan Frederik Meursing, who also guaranteed the lowest coal consumption per horsepower. But Van der Thoorn was not impressed by Meursing. His Amsterdam shipyard 'De Nachtegaal' ('The Nightingale') came across to Van der Thoorn as rather shabby. But the Department overruled him and awarded the commission to Meursing. This proved to be a financial disaster for Meursing, who, as Van der Thoorn had feared, was unable to live up to his low bid. Ultimately, he would incur a loss of twelve thousand guilders on the Christiaan Brunings.

Meursing had experience building steam ships, but this was his first icebreaker. He delved into blueprints of similar ships, and his draughtsmen eventually sent a total of twenty-four construction drawings to the Department for approval. These drawings documented every part of the ship's construction, which was quite unusual for the time; ships were then still generally built without plans.

The Christiaan Brunings was to be an oploper, a ship with a sharply rising bow and a draught of only 20 cm at the front. One of the Department's requirements was that the bow had to be higher than that of the Achilles, which had always had problems with water splashing over the bow. The stern had to be designed to channel as much of the ice as possible away from the ship's propeller. The fore and aft peaks had reservoirs that could be filled with water to 'trim' the ship, or balance her in the water. A steam pipe warmed these reservoirs to keep them from freezing.

the Christiaan Brunings in 1900 after the launch at the dock of J.F. Meursing

steel and steam

At the end of the 19th century, the industry was switching from iron to steel and the Christiaan Brunings followed this trend. Parts such as the 'ijsscheen' (the rising section of the ship's underwater profile), the crossbeams, and the deck beams were made from Siemens-Martin steel up to 13 mm thick, but for the rest of the ship conventional wrought iron was used – steel-like, but structurally inferior. The four-bladed propeller was cast in steel to allow it to withstand hard knocks from the ice.

Because the crew (captain, first officer, engineer, stoker and two deck mates) had to stay on the ship around the clock during icebreaking operations, the Christiaan Brunings had steam and boiler heating from fore to stern, and additional stoves for heating in most of the rooms. The ship also had three 'privies with flush toilet systems and urinals.' The cabin was made of mahogany; everywhere else, the wood was painted pine.

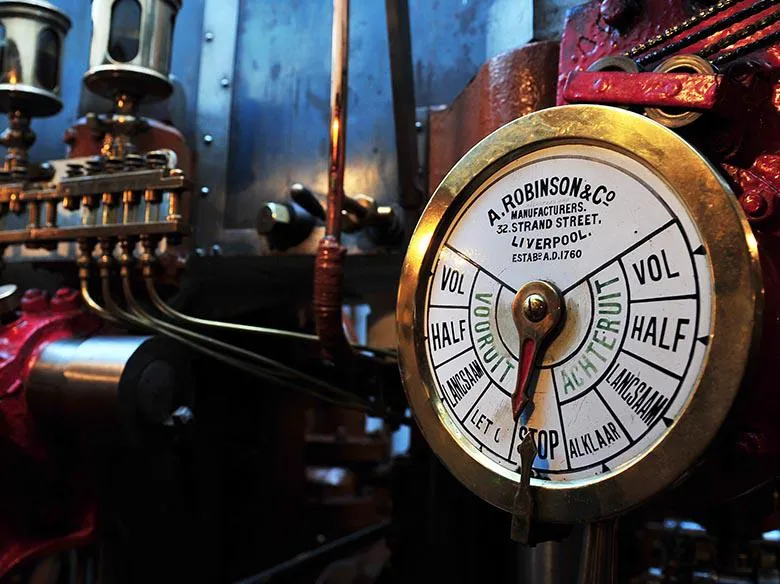

The most expensive component of the Christiaan Brunings by far was the steam engine, coming in at exactly 16,064.48 guilders. The design is what is referred to as a compound engine or steam vacuum engine, with Scottish boiler (another 7,882.56 guilders) and high and low pressure cylinders.

This type of boiler was an invention of Scottish shipyards; it was a good deal shorter than its predecessors, but as the photographs show, it was still an enormous piece of equipment. The boiler's 'heated surface' is 90 m2. The Christiaan Brunings is now on her third boiler.

The steam chamber of the Christiaan Brunings

getting to work

Sailing from her home port of Dordrecht, the Christiaan Brunings got straight to work in the cold winter of 1901. But she would not see truly icy conditions until the very cold winter of 1917, and then again in 1929, which went down in history as one of the coldest winters of the century.

In the summer of 1915, at the outbreak of World War I, the Christiaan Brunings was commandeered for military service, and was used to guard the coastline. She was by no means the only government ship to do this; the navy preferred such ships as they were less conspicuous. After the first few months of the war, the navy began using the Christiaan Brunings as a supply ship. The Department sent several letters requesting the return of the ship but only got her back in 1919, although it must be noted that the navy did have the courtesy to give her a fresh coat of tar and paint, as well as perform some other major maintenance before returning her.

The Christiaan Brunings spent most of World War II docked in Maassluis, usually at the 'Zorg en Vlijt' shipyard and machine works. In late 1944, when the German military requisitioned virtually all the steam and motor craft in and around Dordrecht, she was hidden along with many other ships down a branch of the Meuse near Heenvliet. In January of 1945, she was hit in a British air raid, suffering heavy damage to her superstructure and sustaining a hole in her hull below the waterline. Only quick action on the part of the crew as they escaped kept the ship from sinking. She was later repaired at Zorg en Vlijt, at a cost of eight thousand guilders.

On 2 February 1953, while being used to evacuate victims of the disastrous flood of that year, she ran aground on a large sandbar between Stellendam and Hellevoetsluis, and the evacuees on board had to be transferred to another ship. A week later she was back in service, and on 11 February she carried Queen Juliana to Zierikzee to view the disaster area. The Christiaan Brunings remained active in the area until mid-March, performing sounding for the repair works.

By this time she had been a sounding vessel for many years, first sailing out of Hansweert and then later from Hook of Holland. She had not served as an icebreaker since long before the war. She was sailed by officials from the Research Service for Estuaries, Maritime Rivers, and Coasts (founded in 1930) collecting data on river and tidal flows, fresh/salt water boundaries, silt deposition, sandbars, and ice transport. After the war, she was never used again as an executive vessel, because she was too cumbersome and 'not fittingly furbished'. To make her better suited for her sounding work, in 1951 her original cabin was replaced with her current cabin with more windows. By this time the Research Service was very happy with the ship, which they found much better for sailing than their more modern, 'shuddering' motorboats.

The Christiaan Brunings was relied on very heavily in the preparatory activities for the Delta Works. Engineers sailed her while performing research on flow and bottom conditions in preparation for the engineering of the new estuaries. The Christiaan Brunings was part of the Delta Service North fleet, and at that time sailed from Hellevoetsluis. By 1957, the Department had already commissioned her successor, the Professor Lorentsz, but that ship was only delivered in 1968, and the Christiaan Brunings continued to sail in the intervening years. In that time she underwent two major renovations, with a total price tag of NLG 51,000.

Source: Elisabeth Spits. S.S. Christiaan Brunings, Walburg Press, 2000.

In 1966, the Delta Service asked the owners of The National Maritime Museum's collection, the Vereeniging Nederlandsch Historisch Scheepvaart Museum (Dutch Historical Maritime Museum Society), whether they were interested in taking the Christiaan Brunings, in order to save her from the scrapyard. This was exactly the period in which the Society and the museum were coming to appreciate that even objects from the recent past had potential historic value, and they saw the Christiaan Brunings as a beautiful example of the steam age. The sale was finalized two years later. At that point, the museum had moved from its location on Cornelis Schuytstraat to its present location, the Arsenal at Oosterdok, where there was a place for the ship. The Society was able to purchase her with the support of several large Dutch shipyards. When she changed hands, J.J. Pilon, who engineered the sale, gave the buyers a number of tips, including the following: 'Every other day, idle the main engine and move the throttle to full ahead and full astern, otherwise the throttle may stick.'